Mark Haworth-Booth tells us that, from the beginning, photography has used landscape as one of its richest subjects. By the end of the nineteenth century every corner of Britain's landscape had been documented and soon most of the rest of the world's landscapers would be photographed. (Haworth-Booth, M. 1975)

He says that the question of technique can be merely a confusing issue; Minor White (Plate 46) refused to go into details of camera, film developer, settings, simply saying "The camera was faithfully used"; Cartier-Bresson just said, "Who Cares?".

|

| 1. Plate 46; Edge of Ice, 1960, Minor White |

|

| 2. Plate 7. Castille, 1953, Henri Cartier-Bresson |

On the other hand, Haworth-Booth quotes Ansel Adams, who believed in a good command of technique and famously previsualised his images, and said,"It is futile to visualize the mechanically impossible; we cannot perform on the violin and expect the sounds of a full orchestra." (Haworth-Booth, M. 1975)

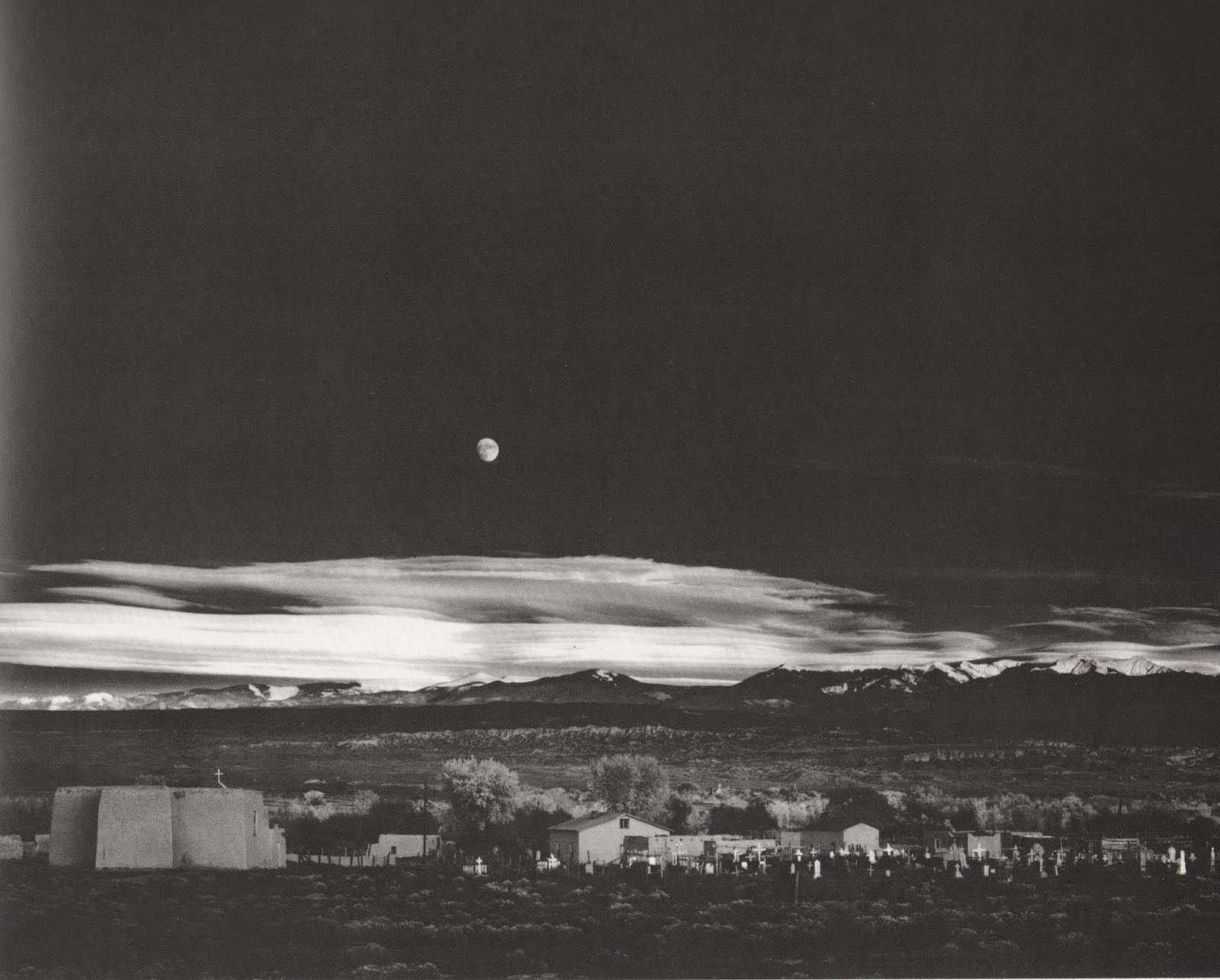

Mark Haworth-Booth goes on to describe the American tradition, where images were sharp all over, with a full range of tones as exemplified by the Group f64. An example of the 'classic' photograph is Mono Lake by Brett Weston (Plate 8), or those by Ansel Adams (Plate 1) and Edward Weston (Plate 10).

|

| 3. Plate 1. Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1944, Ansel Adams |

|

| 4. Plate 10. Oceano 1936, Edward Weston |

Mark Haworth-Booth suggests that the credit for the development of the new tradition belongs to Alfred Steiglitz (Plate 38) and Paul Strand (Plate 13) and was born out of the Pictorialist tradition as exemplified by Edward Steichen's gum bi-chromate print 'The Big White Cloud' (Plate 39). (Haworth-Booth, M. 1975)

|

| 5. Plate 38. Equivalent, 1936. Alfred Stieglitz |

|

| 6. Plate13. Tir A'Mhurain, South Uist, 1954. Paul Strand |

|

| 7. Plate 39. The Big White Cloud, Lake George, New York. 1903. Edward Steichen |

Haworth-Booth posits that, through the work of Paul Strand, photography became itself again after the Pictorialist era; he feels that Strand gave photography back its past, as well as its present and future. (Haworth-Booth, M. 1975)

Aaron Scharf in his essay 'The Gospel of Landscape' goes into great depth on the thoughts and philosophies of Ruskin. In his final sentence he leaves us with "...... Despite this, with his (Ruskin's) extraordinary sensibilities for nature and art and all visual representation, he has bequeathed to us an elaborately structured philosophy about landscape, which still stimulates and provides a key to the understanding of the photographs reproduced in this book. (Scharf, A. 1975)

Keith Critchlow writes movingly, in his essay 'Return from Exile', about environmental issues facing the world in 1975 and how landscape photographs help and play their part. I wonder what he thinks of today's world? He obviously has an affinity for Native American Indians and begins with this beautiful quote from a chieftain of the Blackfeet Nation:

" Our land is more valuable than your money. It will last forever. It will not even perish by the flames of fire. As long as the sun shines and the waters flow, this land will be here to give life to men and animals....You can count your money and burn it within the nod of a buffalo's head, but only the Great Spirit can count the grains of sand and the blades of grass of these plains. As a present to you, we will give you anything we have that you can take with you; but the land never!"

This is a timely reminder today. Although we know now that the sun and our world are finite, they will outlive the human race. The planet has an amazing capacity for recovery; you only have to look how nature has reclaimed deserted post communist factories, silos and even towns in Romania, Hungary, The Ukraine and other Eastern Bloc countries. Critchlow refers to Rachael Carson who reminded us in the 1960s that "All Flesh is Grass". On industry and the use of the Earth's resources, he remnds us that, "One proof of the fallacy of regarding the land as mere chemistry is that man can distil many chemicals from crude oil, but he can no more create the crude oil than he can synthesize one handful of soil. It took millions of years for nature to lay the irreplaceable carpet of soil on our land; it can take one season of ignorant farming to denude it." In the essay he continues to press his theme of a planet in delicate balance by referring to the philosophies of past civilizations and again native American Indian tribes. He gives us another beautiful quote from Walking Buffalo, who in 1957 at the age of 87 visited London from Canada as a representative of the Indian peoples and said, "Living in a city is an artificial existence. Lots of people hardly ever feel real soil under their feet, see plants grow except in flower pots, or get far enough beyond the street light to catch the enchantment of a night sky studded with stars. When people live far away from scenes of the Great Spirit's making, it's easy for them to forget His laws." Keith Critchlow concludes his essay by suggesting that beautiful photographs may be only mechanically recorded visions of a sensitive eye yet they remain mute witnesses of this intimate connection that we can (should - my word) make with the land. (Critchlow, K. 1975)

Keith Critchlow's essay, in particular, as well as the other essays and the introduction to this book resonate deeply with me and fit in especially well with my work for Assignment 3. The writings of both Robert MacFarlane and Roger Deakin are providing much inspiration for my third assignment. They are not photographic books but environmental ones and echo the words of Keith Critchlow.

And what of my favourites? Ansel Adams would always be near the top of my list and the image included in the book is a favourite; I especially like the rich, contrasty, black and white tones. Although I am a fan of Edward Weston, this particular image would not feature on my list of favourites. I really like Paul Strand's Tir A'Mhurain and, being a lover of the far north west of Scotland, would buy the book if I had the money. I like the stark blank and white of Albert Renger-Patzsch's Fields in Snow (Plate 33) from 1956. Giorgio Lotti's Mare, 1970, Plate 34 reminds me of ICM images, which fascinate me at the moment. Bill Brandt is being very modest including only one of his own images and I find it interesting that he has also chosen an image from Scotland's north west for plate 35, Sky Mountains, 1947. I really like the grainy moody atmosphere in this; the grain is reminiscent of the droplets of water in the mist laden air. Finally, I could never pass up one of Fay Godwin's images and Ridgeway, Barbury Castle Clump (Plate 43) from 1974, is typical of her work. These are just a few of my particular favourites, but Bill Brandt has made an excellent choice. Interestingly Mark Haworth-Booth says that he worked at top speed and rarely altered a decision when making and sequencing his collection. (Haworth-Booth, M. 1975)

|

| 8. Plate 43. Ridgeway, Barbury Castle Clump, 1974, Fay Godwin |

|

| 9. Plate 33. Fields in Snow, 1956. Albert Renger-Patzsch |

Boxer, S. (1996) Photography Review; How Ansel Adams Put Nature in Focus [online]. The New York Times. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/08/arts/photography-review-how-ansel-adams-put-nature-in-focus.html [Accessed 9 June 2014]

Haworth-Booth, M. (1975) The Land; Twentieth Century Landscape Photographs London and Bedford: The Gordon Fraser Gallery Ltd.

Scharf, A. (1975) The Gospel of Landscape The Land; Twentieth Century Landscape Photographs London and Bedford: The Gordon Fraser Gallery Ltd.

Critchlow, K. (1975) Return from Exile The Land; Twentieth Century Landscape Photographs London and Bedford: The Gordon Fraser Gallery Ltd.

Bibliography

Deakin, R (2007) Wildwood; A Journey Through Trees 2nd Edition London Penguin Books

MacFarlane, R. (2007) The Wild Places 2nd Edition London Granta Publications

No comments:

Post a Comment